Among my civilian friends there is some confusion over how a musician uses the words, practice and rehearsal. For musicians, practice is always a verb (we don't say "I'm off to opera practice."), is always done alone, and makes up the raw materials on which we draw as professional performers. Rehearsals, on the other hand, are what we do to prepare concerts as an ensemble. Since it's the most consistent example, I'll site a symphony orchestra schedule. For a weekend's set of three performances, the orchestra will have four rehearsals each lasting 2, 2.5, or 3 hours. Individual musicians are expected to show up at the first rehearsal able to play and interpret the entire program. Depending on the music, this could take one hour or many. If one is preparing to play a concerto, a chamber concert, or an audition, weeks or months of dedicated practice is necessary.

For a musician, individual practice is much more than preparing for performances. It is the essential stuff that makes up our musical identity. As we mature, we learn to be better practicers, to focus our work and be efficient. However, efficiency alone cannot replace what we learn from spending hours alone with our instruments and in repetitive contact with musical phrases. Interpretations, individual style, poise, and artistry are all the result of hours in the practice room.

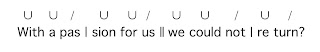

What does a musician practice? Everyone has fundamentals which require daily attention. Basic issues of technique, intonation, articulation, dynamics, and tone quality are addressed in daily repetitions of scales (do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, si, do) and exercises based on common scale patterns (do, mi, sol, mi, do or do, mi, re, fa, mi, sol, etc.). These repetitions are most profitable when done with a metronome, or as we call it, a "lie detector." Musicians who do not have to make their own reeds often have etudes that address other technical issues and receive regular visits. Oboists and bassoonists have etudes, too, however professional schedules require such a volume of reeds, that time at the reed desk gets significant priority. After the fundamental work, a musician's practice time will be led by the demands of future programs. Learning and interpreting a piece of music requires both the development of muscle memory and learning the music "by heart." You must know what's coming and what you're going to do with it, as well as how to execute a particularly gnarly technical passage. The most arresting performances happen when the music seems to flow directly from within the musicians. For it to come out that way, it first has go in. Practicing is how this is done.

A new piece of music, may reveal certain deficiencies in your fundamentals regime. A number of years ago Zéphyros was playing a piece by Lalo Schifrin that had a nasty passage of fast, short, articulated notes. The woodwind technique for executing such a passages has the rather indiscreet name, "tonguing." I had a pretty fast tongue (we talk like this all the time, believe me . . .) but I needed to spruce it up for this passage. So I added certain exercises to my daily practice that addressed my tonguing deficit. As bodies age, certain technical issues crop up. As I've gotten older, I find that the evenness between my middle finger and ring finger on my left hand isn't as dependable as it once was. So that has become another thing addressed with practice. In many ways, as a musician matures, the ears get more sophisticated and so the standard one holds as a goal can become quite rarefied. This sense of the unattainable in the art we love inspires musicians through the many solitary hours spent with their instrument and metronome. Those of us with Sunday School backgrounds will remember Jesus' "Parable of the Talents." Gifts come with responsibilities. Shirking them shows ingratitude.

Those of us with Sunday School backgrounds will remember Jesus' "Parable of the Talents." Gifts come with responsibilities. Shirking them shows ingratitude.

With that in mind, perhaps my next posting should be titled, "PRACTICE vs. BLOGGING."

From “Elegy for an Artist” Part 4.

“Still (A year)” by C. K. Williams

A year, summer again,

warm, my window open

on the courtyard where

for a good half hour

an oboe has been

practicing scales. Above

the tangle of voices,

clanging pans, a plumber’s

compressor heretically

intensifying,

it goes on and on,

single-minded, patient

and implacable,

its tempo never

faltering, always

resolutely focussed

on the turn above,

the turn below,

Goes on as the world

goes on, and beauty,

and the passion for it.

Much of knowing you

was knowing that, knowing

that our consolations,

if there are such things,

dwell in our conviction

that always somewhere

painters will concoct

their colors, poets sing,

and a single oboe

dutifully repeat

its lesson, then repeat

it again, serenely

mounting and descending

the stairway it itself

unfurls before itself.